Author: Dr. Kahler Stone, MPH, Assistant Professor at Middle Tennessee State University

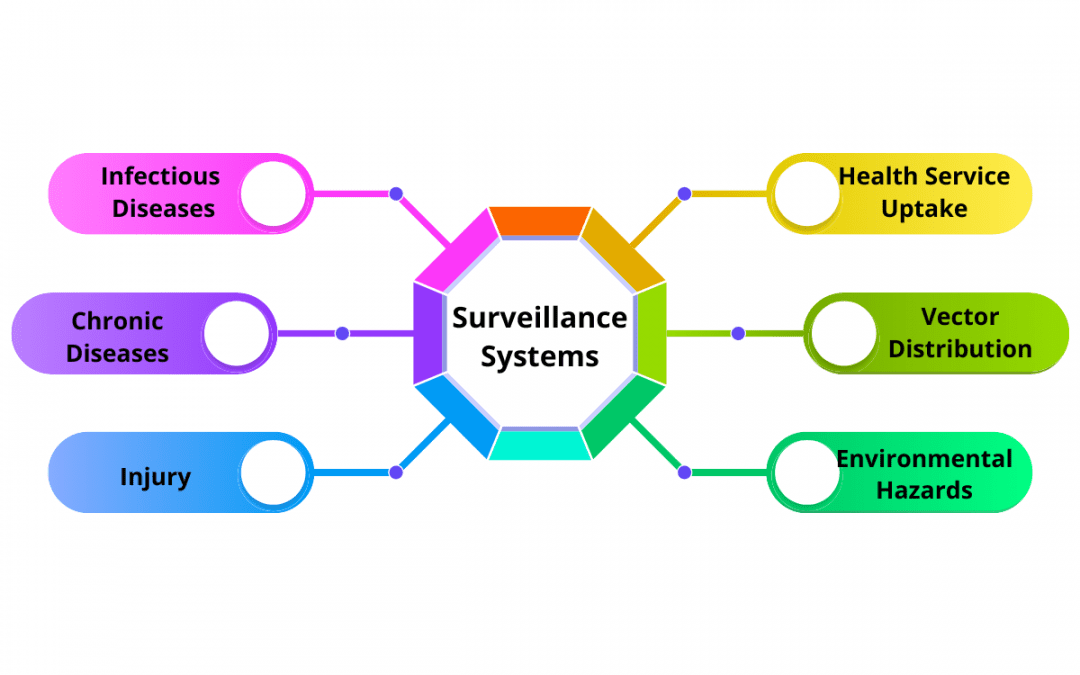

We’ve already established that each public health surveillance system is unique in structure and purpose. Three simple and meaningful questions can be asked to understand the system’s usefulness.

- Is it timely?

- Is it complete?

- Is it communicated?

If the answer is no to any of these, an effort should be made to improve it! Why these three questions? Well, though they are not exhaustive questions, they are a great starting point to understanding the utility and function of a system.

Is it timely?

Timeliness refers to how quickly information is reported and transferred. This can be measured in different ways, but most importantly, does the metric make sense for the health condition under investigation?

Here’s a simplified example. Several gastrointestinal (GI) illnesses are routinely reported and tracked in a passive surveillance system when a case patient comes in contact with a health professional. That health professional will either report the GI illness directly to the local or state health department or send a specimen from the case patient to a laboratory that then reports the positive tests to the health department. Once the health department receives the report, staff will further investigate by follow-up phone calls or interviews, then report and transfer that information to the CDC. These data on case patients passively roll in from reports from providers or laboratories and are then analyzed on a rolling basis at local, state, and national levels to see the status of that particular type of GI illness. In this example, each of these steps seems like it could reasonably be accomplished within days to weeks.

Back to our question, is that surveillance system timely? We can answer that question by understanding how long it takes for someone seeking care to be reported to health officials, then how quickly follow-up investigations take to when it is finally reported and analyzed at the state or national level. These time intervals tell us how quickly the surveillance system operates. If a particular communicable disease has a median incubation period of 4-5 days, we know that for every 4-5 days that our surveillance system is not giving us the situation report, that disease is spreading under our noses without us knowing!

Is it complete?

Completeness can refer to two things in a surveillance system:

- Is the system sensitive enough to capture most or all of the cases in the population?

- Are the data captured on the cases and reported into the system whole, or is it missing crucial information about the case?

Following along with the GI illness example, if our surveillance system only captures a fraction of occurring illnesses in the population, we’d say it is not complete, thus hindering our health situational awareness. In this regard, one way to assess the completeness of a system is to conduct follow-up studies with a subset of facilities and clinics and review health records to reconcile the cases reported and captured by the surveillance system, which was only found upon additional review. It is also important to understand how complete the data are on those reported cases. It is not uncommon for demographic variables to be missing from routine passive surveillance systems. This is a sign of incompleteness in the system and is important to improve prevention and control efforts.

Is it communicated?

Remember, public health surveillance has to inform disease prevention or control. In other words, it has to lead to action if necessary. If the data from a surveillance system is not timely, the control measures and actions that can be taken are limited and are in a reactionary space. If the surveillance isn’t complete, in terms of underreporting diseases or not having all the pertinent information on cases, your options as a health official are limited in scope and size. Nothing will be done if the health intelligence is not shared or communicated. You don’t know (or do in this scenario) what you don’t know.

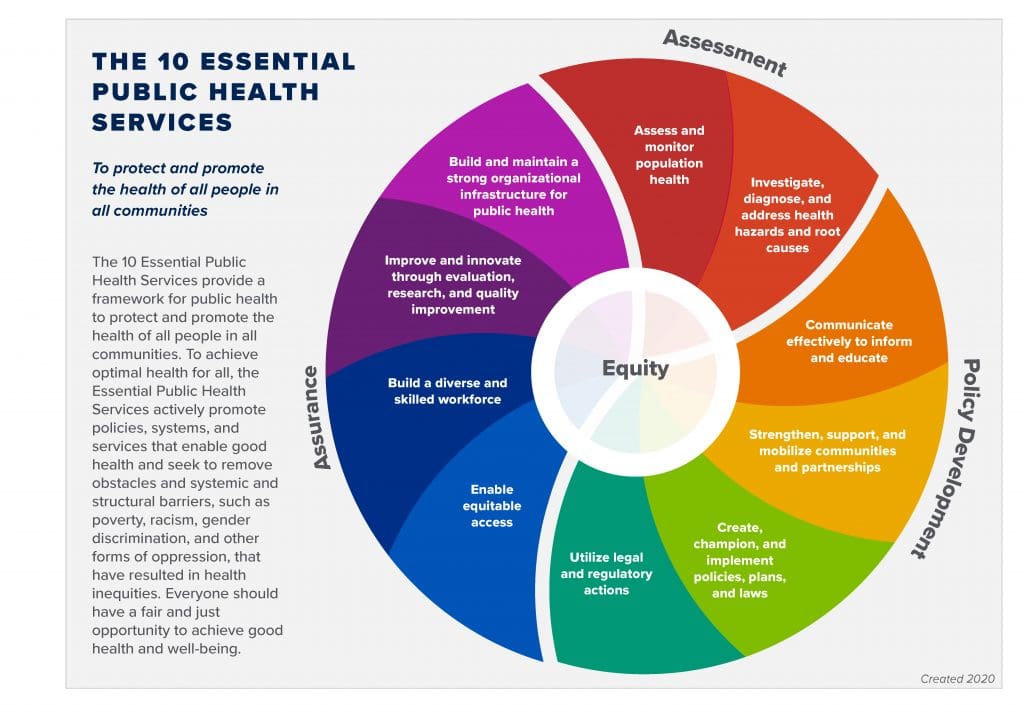

Our question of is the system actionable stands alone though, even if the system is timely and complete for the most part. If the system is not understood by its users and consumers and communicated clearly with decision-makers and stakeholders, then the surveillance system is as good as dead. The first two Essential Public Health Services (EPHS) relate directly to public health surveillance. If the system is not understood and communicated, the following EPHS #3 is hindered. It is critical that whatever the surveillance system, it is properly resourced to analyze, communicate, and disseminate the intelligence coming from that system for public health action.

Source: CDC

Resources:

- What’s Public Health Surveillance and is it Useful blog post

- CDC Introduction to Public Health Surveillance

- Smith PF, Hadler JL, Stanbury M, et al. Blueprint version 2.0: updating public health surveillance for the 21st century. J Public Health Manag Pract 2013;19:231–9.

- Introduction to Evaluating Surveillance Systems (On Demand-No CE)